Ian Hamilton Biography

Ian Hamilton: A Life in Art

1

The first artwork I remember doing was

a watercolour of a green field dotted with white flowers (daisies

as in those little white flowers we made daisy chains out of).

That was in prep 1 at Wooloowin State School and it was exhibited

proudly in class. That painting, long disappeared, still evokes

in me the sense of wonder I felt at the time. I can still see

those little white flowers dotted across the green, can almost

smell the grass! No artwork since has affected me as much.

Through the early years I drew people and planes and boats and

trains but the drawing my mother would often comment upon was

of the family cat. Apparently that was special. Later in primary

school I immersed myself in a subject called 'Geometric and Perspective

Drawing', learning about vanishing points and other technical

terms. One drawing I particularly recall was of a caravan done

in the Geometric style, which meant angles of 45 degrees and

weird perspectives. Like the flower-dotted field that drawing

has long disappeared. One of the only remaining drawings from

this time is of a fish leaping to catch a frog done on the inside

cover of the 'Eagle Book of Trains', which I still have. I'm

not sure about the fish or the frog but I retain an interest

in railways.

At Kedron High School I did a drawing of futuristic cars on a

black background that was exhibited along with pretty landscapes.

It was pretty good and everyone thought I'd end up working for

General Motors as a designer.

As a teenager I studied art part time, including a brief period

with a life drawing class led by the legendary Mervyn Moriarty

(who later formed the Queensland Flying Art School). For my first

lesson I took along a small sketchbook. and pencil and was embarrassed

to find everyone drawing with blocks of charcoal on huge bits

of paper. That was my first real lesson. I also studied briefly

under Roy Churcher at the same campus where I was studying for

my electrical apprenticeship and (part-time) electrical engineering

(I would run into Roy sixteen years later when I went back to

Brisbane as artist in residence at Griffith University and again

in 1999 when Betty Churcher came to Mildura to do a TV program

on the Mildura Art Centre's Degas pastel).

When I was eighteen I went to Mt Isa to complete my apprenticeship

and continue part-time Engineering studies. I found myself at

one stage being taught art by a mad Balt who later topped himself

(Mt Isa seemed full of mad people). He tried to teach a European

version of landscape that I rejected. In Mt Isa there were few

Autumnal leaves and even fewer snow-covered mountains. There

were, however, opportunities to discover a landscape of despair.

On one occasion I was returning a friend's old Bedford truck,

from a dam site just beyond the Northern Territory border, and

took a wrong turn. I ended up with very little fuel, at an abandoned

outstation. When I switched off the engine and got out I felt

an immense silence. I hadn't felt anything like that before.

What I saw was a deserted shed and a dry dam ringed with dead

cattle. That was frightening. Many years later I would visit

another dry dam site north of Mildura that would become a favourite

spot for drawing and which would inform my later drawings along

the dry eastern escarpment of the Adelaide Hills.

In the summer of 1961 I returned to Brisbane

for a holiday, to find my father dying of cancer. I was with

him when he died. I didn't go back to Mt Isa but finished my

apprenticeship in Brisbane. I went wild after that. I joined

the Alexandra Headlands Surf Lifesaving Club. For the next few

years I would winter in Sydney and return to Brisbane each summer

for the surfing season. In 1967 I spent time as an Electrical

Engineer, on a Swedish merchantman, travelling the Pacific Rim.

It was in San Francisco that I purchased my first Bob Dylan album.

Dylan was for me a visual artist; his compositions as much movies,

or enigmatic paintings, as songs.

When the ship returned to Brisbane I left

and returned to my old workplace at the Evans Deakin shipyards

at Kangaroo Point. It was there that I met Ted, a communist union

official who would have a profound impact on me. He introduced

me to the Foco Club, a left-wing organization that ran Sunday

night events at the old Trades Hall. He also introduced me to

John Dos Passos and his trilogy USA; a book that left

a huge impression.

In mid 1968 I met Jennifer Walker, a young teacher from Adelaide.

Before a year was out I moved to Adelaide and we married in 1969.

It was while studying art, part time at the South Australian

School of Art, that my lecturer, Virginia Jay, convinced me to

apply for full-time entry, which I did.

I did well at art school but something happened at the end of

third year that was to change my direction. During the Christmas

break between third and fourth year I was working in a factory

repairing fluorescent light fittings. One lunch hour I left one

of the repaired fittings turned on in the corner of the workshop,

turned the main lights out and left to buy some food. When I

returned I couldn't help but notice the fitting glowing in the

corner. I liked what I saw. It was at that moment I decided that,

on returning to art school for fourth year, I would use the fluoro

tube as a painting medium.

This would lead to work that some saw as being influenced by

Dan Flavin, but which in reality had much more to do with my

own background (including the perspective drawings all those

years ago) and with colourfield artists like Barnett Newman.

Where Newman used paint strips to define spaces between colour

fields I would use fluoros, arranging them on grounds such as

fabricated boards and carpet underfelt. This led to a series

of new works that would be displayed in the art school (Art

School??) gallery and outside the school.

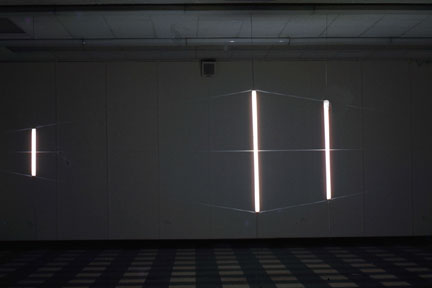

Perspective Grid' from the Light, Colour Space exhibition, SA

School of Art gallery, 1974.

Perspective Grid' from the Light, Colour Space exhibition, SA

School of Art gallery, 1974.

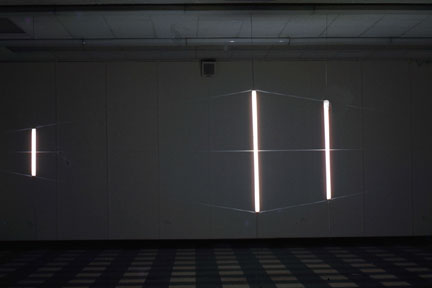

LIght, Colour Space exhibition, Contemporary Art Society gallery,

1974.

LIght, Colour Space exhibition, Contemporary Art Society gallery,

1974.

As a result of the exhibition I was offered

a show at a well-known North Adelaide commercial gallery. However

Art School policy forbade students showing at commercial galleries.

Disappointed, I sought other venues. Late in the year I was given

permission by the Australian Wool Commission to hold an exhibition

in one of their old woolsheds at Port Adelaide. The exhibition

'Light - Space - Colour' pitted fluoro installations against

the light coming through cracks and openings in the building's

cladding, doors and windows.

The Adelaide Advertiser critic Ivor Francis wrote:

It is unethical and unwise for a critic to single out for

special comment the work of a student attending art school.

Ian Hamilton is an exception. He has received official approval

for an exhibition and an investigation of public reaction to

it as part of his final year diploma course at the SA School

of Art.

His medium is the fluorescent tube by means of which he explores

space and colour and, by combining it with other objects, such

as string and hessian, sees if they can all be made to fit together

into a particular environment.

This aim differs from Dan Flavin's systematic corner installations

in the "Some Recent American Art" exhibition at the

Art Gallery of SA.

With a grand imaginative gesture of Michelangelonic proportions,

Hamilton has used a vast, empty woolshed (No. 32) which is at

Bedford Street, Gilman, and belongs to the Australian Wool Commission.

It is a building pregnant with spine-chilling, surrealistic possibilities

such as would have delighted the 18th century painter Giovanni

Piranessi in his search for the macabre among the dungeons of

ancient Rome.

In this atmosphere of suspense and emptiness, among a forest

of timber pillars streaking high up into the hovering gloom,

Hamilton strung a vertical, blood-red fluorescent tube. As he

looked back from the far-distant end of the shed, the tube peeped

at him balefully, disappearing and reappearing eerily from behind

one or other of the posts as he moved.

Using this as a starting point, he strategically added other

tubes of different colours which, together with string wound

around the pillars and bits of dangling hessian has produced

the uncanny effect of turning the perspective topsy-turvy.

The result is a hard-to-describe but exciting total environmental

kinetic experience for anyone able to enter into the spirit of

it.

However, if you view it only for the purpose of arguing whether

it is art or not, you may just as well expect recompense for

the bodily harm you may receive while precariously scrambling

up tooth and nail into the woolshed to see it.

Others must have taken note because, prior

to graduating I was advised that I'd won an Australia Council

'Living Artist' fellowship for 1975. This allowed me to continue

work on light and space.

My next exhibition was at the Experimental

Art Foundation. Adelaide Advertiser art critic Nigel Murray-Harvey

wrote of the exhibition:

Ian Hamilton's work with wool, fluoro tubes and skylights,

at the Experimental Art Foundation is immensely refreshing.

Two groups of fluoros, half hidden in greasy wool, seem at first

to be pools of bright sunlight admitted by the two small skylights

high in the bare corrugated asbestos roof of the partitioned-off

corner of the former jam factory.

It feels good to be there and the lack of motes floating in the

shafts of light, which 'should' be there, makes much of the space

between the skylights and their pools of light.

Of the same exhibition Stephanie Britton wrote:

With sheep sheering never too far away in Adelaide these days,

art lovers are able to join the fun, though in a somewhat different

fashion.

Ian Hamilton, young local artist whose work with fluorescent

light began while a student at the SA School of Art has produced

an environmental piece at the Experimental Art Foundation, using

wool and light.

Basically it is about a simple optical illusion and although

it works beautifully, to describe it in detail would remove the

element of surprise for those who have not yet seen the show.

One can say however, that he uses the roof structure of the Jam

Factory with its skylights, some fluoro tubes and a large quantity

of fleece.

It is a work of great charm, sensuous with all that lanolin-smelling

wool underfoot against the stark white walls and iron roof.

Like a Magritte painting it relies on an innocent appearance

and a sudden double-take, though Hamilton's revelation is a purely

physical one to do mainly with a natural phenomenon albeit reinforced

by art.

The fact that the Jam Factory happens to have skylights nine

metres off the floor is one of the unforseen bonuses of that

eccentric building.

Stephanie Britton also wrote, in the publication 'A Decade at

the EAF':

The conjunction of the new upstairs EAF gallery space and an

artist with an interest in the modification of space with light

led to perhaps the most successful use to which the gallery as

a sculptural space was ever put.

He filled the floor with piles of lanolin-smelling fleece and

below the 9 metre high factory sawtooth roof skylight he embedded

a 'daylight' fluoro. Since the tube (tubes) appeared to have

the same dimension as the skylight the illusion was complete.

The effect on a dull day of the bright patch of light on the

floor was strangely powerful.

In 1976 I was appointed Artist-in-residency

at Griffith University in Brisbane for twelve months. Here I

continued work on light, mounting installations at the university

and at the Institute of Modern Art, in the city.

Of one exhibition at the IMA, Sunday Mail critic Betty Churcher

wrote:

At the Institute of Modern Art, two situation pieces provide

a new experience for Brisbane. Both have been shown before in

Adelaide, but I'm sure not more successfully than they are now

in the simple white cubic space of the Institute.

In the upstairs gallery, Ian Hamilton creates a more evocative

and visual situation out of the double doors of the warehouse,

some fluoro strip-lighting and a floor covered in raw wool. The

access doors are just parted to allow a thin strip of sunlight

which is simulated by the fluoro strip under the wool floor cover

- a truly trompe-l'il effect which continues to confuse the observer

long after the real sun has set.

However, my most interesting work was being

done (un-reviewed) at the University. Taking the concepts used

in the woolstores show in Adelaide a step further, I installed

a series of fluoro light works in the forest surrounding the

university campus. Most successful of these was the fluoro cube.

Strung from high branches of the tall gum trees this fragile

work would rise and fall up to three metres as the supporting

trees moved in the wind. However, the university safety officials

didn't take kindly to bare fluoro tubes strung on and around

trees so the work was banned. The filmmaker David Perry (also

artist in residence at the University) filmed the dismantling

of the cube. Other art pieces included long strips of coloured

fluoro tubes up the trunks of trees. At night these produced

a spooky effect that drew the viewer deep into the forest. Other

works produced at the university included experiments with perspective

using string, laser beams and fluoro tubes. The best of these

did indeed alter the viewer's spatial perception.

But I was ready to move on from fluoro

work. While at Griffith University I'd developed an interest

in ritual through the anthropological work of Victor Turner (who

I had studied at art school) and a fascination with entropy and

paranoia, partly through reading Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow.

Perhaps looking for a way out of the fluoro tube work I presented

a piece at the then Art Gallery of Queensland, to a group of

mainly gallery 'friends'. Before a seated audience, and supported

by slide and video projections portraying the action one second

ahead of my real time performance, I placed a flouro tube on

the floor, wired it and turned it on. All this was done very

slowly. When the tube was lit I left the stage and returned with

a rock. This I held over the tube for some seconds then dropped

it. This caused a huge explosion, giving some in the audience

a huge shock. Having done this I pointed to the floor where the

rock sat among the debris of broken tube (both ends strangely

intact) and left the stage.

This performance signalled the end of my involvement with fluoro

tubes as a primary art medium.

During that same period I went to Lamington Plateau where I saw

bowers of the Satin Bowerbird (Ptilinorhynchus violaceus). I

was taken by the complexity of the male bird's display and behaviour.

I saw, in the construction and presentation of the bower, elements

of both design and ritual, and a strong sense of colour. While

filming one male bird building his bower I observed the bird

stepping back from the bower, critically examining what it had

just done, then racing back in to change it. This seemed a calculated

action and not unlike the way artists work. I also observed so-called

'playgrounds' of Tooth- billed Bowerbirds (Scenopoeetes dentirostris).

While not as elaborate as the structures of Satin Bowerbirds

these settings, made from overturned rainforest leaves, made

for a kind of stage, upon which the male bird performed.

Back in the University studio I assembled my own 'playground'.

It consisted of a circular mound of leaf litter about two metres

across and 20 cm deep, above which was suspended a yellow fluorescent

tube (yes, the tube had reappeared). Around the walls I placed

photocopy assemblages of images of various recent artworks and

quotes from recent readings on art, entropy, paranoia and light.

Two lasers directed beams across the stage so that when I sat

on the stage (dressed in black and wearing a papier-mâché

bird's head) two pin points of red light appeared; one on my

stomach and one on my back.

Because the lasers were hidden it appeared as if the beam was

going through me.

Insert image of playground

Thus began an obsession that would continue

for many years and that would re-emerge in later years.

In 1977 I returned to Adelaide and began

working as a senior project officer for a commonwealth employment

scheme. In 1978 I received a grant from the South Australian

Government to 'Study the Art of the Golden Bowerbird'. This allowed

me to travel to the Mt Spec area northwest of Townsville where,

over several weeks camped within the forest, accompanied by the

sounds and creatures of the forest (including leeches), I observed

the workings of the male Golden Bowerbird.(Prionodura newtoniana)

Drawings from field notes

Drawings from field notes

Intrigued by the complexity of Golden Bowerbird

display (the male bird sang, mimicked, danced, built and decorated

complex structures) I began to develop a theory about time and

creativity I would later call; Time Allows the Elaboration

of Basic Urges and/or Forms.

The suggestion was that an organism free from the pressures of

predation, hunger, parental duties and territorial disputation

had time to elaborate on basic urges (nest-building) and forms

(the form of the nest).

In mid 1978 I was invited to participate in Act 1 in Canberra

(an event organised by the Canberra School of Art). My piece,

exhibited it in a Canberra park, drew on work I'd done at Griffith

University and the Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane during

1976. It consisted of a circular 'stage' of leaf litter surrounded

by rocks. Above this stage was a yellow fluoro tube hung vertically.

Two lasers directed beams across the stage. Wearing black clothes

and a papier-mâché bird's head I sat on the stage

while my friend and fellow exhibitor Bob Ramsay circled the setting

reciting a prepared text about time and creativity.

Insert image of Canberra work

Later that same year the Institute of Modern

Art accepted a proposal by Bob Ramsay and me to exhibit a performance

piece titled The Brisbane Line; A Ritual Trance Walk. The exhibition

documented a walk we had completed; a walk that led us from an

Aboriginal bora ground (an initiation ritual site) in the foothills

west of the city to a midden on Stradbroke Island. The route

of the walk took us through the ruins of the Holy Name

Cathedral in the city. In passing between two sites of pre-European

culture we would enter the ruins of Brisbane's pre-global (Anglo-Irish)

culture. Documented records of the walk, along with various objects

collected along the way, were displayed in the Institute of

Modern Art.

I retraced that same route two more times; once with my friend

Leo Davis in the Summer of 1979 and again (alone) in the summer

of 1980. The experience would lead to the completion of two novels:

Meanjin Crossing and A Long Walk Through a Short History.

In 1983 the Experimental Art Foundation published The Ceremony

of the Golden Bowerbird: Playground for Paranoids; essentially

a script for performance based

on my experiences in the rainforest and which brought together

several trains of thought, including ruminations on creativity,

science and art.

The

Ceremony of the Golden Bowerbird

The

Ceremony of the Golden Bowerbird

From 1983 to 1995 I was employed by the

City of Prospect, first as the Community Arts Officer, then as

Community Development manager. The highlight of these years was

the opening of the Prospect Art Gallery in 1988, the first purpose-built

local government art

gallery in metropolitan Adelaide. As Community Development manager

I was the driving force behind its design and completion.

In mid 1995 I left Prospect Council to undertake research for

a book about country mayors. With an advance from publishers

Wakefield Press, I set out on a journey around Australia, interviewing

the mayors of country towns across Australia. Heart of the

Country was published 1996.

Heart

of the Country

Heart

of the Country

The 'Western Herald' from Burke stated:

Bourke's Mayor Wal Mitchell is one of 17 rural leaders featured

in

the book "Heart of the Country", the result of author

Ian Hamilton's

exploring what drives leaders of remote communities.

Ian Hamilton is a city dweller and as he watched coastal cities

grow

while inland towns declined, he wondered what went on west of

the

Great Divide, what sustained this country and who was in control

of

its destiny.

So he set out to discover what sort of people took the task of

guiding these areas, making decisions about their future.

As a result, Ian spoke to Mayors, Shire Presidents, Shire

Chairpersons and Wardens, asking what drove them to keep their

remote

corners of Australia alive.

Ian put the stories of 17 rural leaders together, these being

Wal

Mitchell of Bourke, greg Jones of Moree, Ross Miller of Toowoomba,

Barry Braithwaite of Roma, Les Tyrell of Thuringowa, Ron McCullough

of Mount Isa, Jim Forscutt of Katherine, Alan Eggleston of Port

Hedland, Ron Yuryevich of Kalgoorlie-Boulder, Malcolm Puckridge

of

Ceduna, Eric Malliotis of Coober Pedy, Keith Wilson of Whyalla,

Joy

Balluch of Port Augusta, Eric Sambell of the District of

Peterborough, Ruth Whittle of the town of Peterborough, Eddie

Warhurst of Mildura and Murray Waller of the West Coast of Tasmania.

After speaking to these people, Ian concluded that while they

were

different, there was among them a common belief in the ability

of the

individual or the small community to overcome adversity.

These stories, including Wal's, can be read, enjoyed and learned

from

Ian's book "Heart of the Country".

In March 1996 I was appointed Arts

Manager to the City of Mildura. One of the first things I was

asked on arrival in Mildura was, 'when are you going to reintroduce

the triennials?' This was a reference to the highly successful

Mildura Sculpture Triennials. I didn't think

that was a good idea. The Mildura Sculpture Triennials were of

a period, their place in art history was secure and inviolate.

Instead I proposed a contemporary version, one that took into

account recent thinking on matters such as ecology and the state

of the Murray Darling river system and which allowed a wider

spectrum of media. While mulling over what might replace the

Triennials I happened to read a poem by Jennifer Hamilton titled

View From a Plane. It read, in part:

The land lies beneath,

a palimpsest etched

erased and re-etched

by wind and sun and time.

Symbols in ancient script,

knoll and ridge, rock and

scrawl of creek bed speak

of time and space beyond ours.

Twisted and cramped, they

are surrounded by

lacunae, drifts of sand.

A page of Tamil,

mysterious dots, curls and spaces,

signifiers, but..

to us, unreadable.

But it is our land.

So owning it, we carve it.

We slice the ancient

parchment into squares,

triangles, parallelograms,

the straight line rampant.

We push the scattered runes

back into sand and time.

Ploughing and planting

turns the old faded brown

Into sharper greens and yellows.

And then the parchment

Itself disappears

Beneath the patterned crust

Of the city.

The word palimpsest stood out me. It seemed

to summarise my own thoughts about landscape. Indeed, Mildura

was a palimpsest, with its evidence of Aboriginal occupation,

buried irrigation channels and dryland farms changed to irrigated

vineyards. So, in 1998, began Mildura Palimpsest, a highly successful

arts biennial that is still going strong, thanks to the support

of many people. The fourth Palimpsest event in March 2000 coinciding

with the second Regional Galleries Summit hosted by the Mildura

Arts centre. Over one hundred artists from Australia and overseas

participated in this event.

http://www.mwaf.com.au/old_sites/palimpsest/index.html

But perhaps the greatest highlight of the Mildura years for me

was the SunRISE 21 Artists in Industry Project, which

I initiated in 1998. With funding from several sources we were

able to employ a curator (Helen Vivian) and five artists to work

with five industry groups to produce five works of art reflecting

the work of the host industry. This proved to be a In an odd

way what I had seen at the site of the abandoned bower was similar

to what I'd witnessed at the abandoned bora ring and the ruins

of the Holy Name Cathedral

all those years ago while undertaking the Brisbane Line project.

My interest in making serious art was renewed.

I left Mildura in late 200 and returned to Adelaide to begin

a new phase in art making.

Someone once said that 'artists can emerge at any time'. Back

in Adelaide I felt that I was re-emerging as an artist. I began

a series of forays to the escarpment of the Adelaide Hills with

Ken Orchard, making pen and ink drawings of the landscape. Some

of these I

converted to computer drawings using the Microsoft Word 'draw'

facility. These 'computer drawings' were shown at the Station

Masters Gallery at Strathalbyn in June 2002.

The following is an extract from Adelaide

Hills Weekender, July 2002

An exhibition inspired by the landscape near Strathalbyn is

on

display at the Strathalbyn Railway Station during July.

The display comprises the works of Ian Hamilton and Ken Orchard

and

are the outcome of numerous field trips.

Ian Hamilton ........reworked his images. Instead of using natural

materials he decided to transform his images using the computer.

He

took his field sketches and using a mouse and a simple drawing

program he redrew the sketches. The images are quirky but catch

the

feel of the countryside in a unique and deceptively simple way.....

and a simple drawing

program he redrew the sketches. The images are quirky but catch

the

feel of the countryside in a unique and deceptively simple way.....

'Sturt Highway', 2003. 40 X 100

cm. Roadside weeds and dirt on mdf board.

'Sturt Highway', 2003. 40 X 100

cm. Roadside weeds and dirt on mdf board.

In 2003 I began a series of large works

on steel sheets. Laying the sheets flat I applied water, various

acids and urine to create patterns inspired by views of the land

from aeroplanes. Some of these works were shown in the exhibition

'Intimate Topographies' at the Hahndorf Academy (with Ken Orchard,

Pamela Kouwenhoven and Ed

Douglas) in June 2004.

Scan page from journal

But more and more I was drawn back to Bowerbird.

I re-examined my work from the late 1970s and early 1980s and

began constructing studio bowers from sticks found in and around

my home in Adelaide. In 2005 I held a solo show at the Mildura

Arts Centre titled Out of the Forest: Bowerbirds and the Art

of Ian Hamilton. The exhibition included studio sculptures,

large giclee prints, drawings, paintings and field journals.

It was for me the most successful exhibition I'd mounted since

the Woolstores exhibition of 1974.

Image from show

Steve Naylor review

Leo Davis catalogue essay

In late 2008 I went back to the cloud forests

of North Queensland with Leo Davis. We camped at the Paluma Dam.

In the nearby forest, not far from an actual bower of the Golden

Bowerbird, I built my own forest bower. 'No one will ever see

it', Leo said. 'I don't care,' I replied. But I did continue

to make works based on the bower bird for public display (entirely

ephemera as it turned out). These included several installations

at the Palmer Sculpture Biennial and the Heysen Sculpture Biennial.

The last of these was a giant 'maquette' at The Cedars, part

of the Bower Tower Project with John Hayward.

Insert image from The Cedars

In addition to these bower works I have,

over a period of several years, installed several

'memorials' to the bowerbird. One is near Euston in souther New

South Wales, one near Hungerford in SW Queensland, and another

at Mt Spec in far north Queensland.

Avenue Bower # 1 120 x 900 x 60 cm Eucalyptus Sticks 2005

Avenue Bower # 1 120 x 900 x 60 cm Eucalyptus Sticks 2005

Bower 1 Palmer Sculpture Biennial 2008

It's been a long journey since that small painting of flowers

in a field of green from primary school, and I'm still at it!

Must be mad! None of it has ever turned a profit!

As of March 2015 I am working towards completing

two projects with my 'Bower Tower' partner John Hayward. One

is a large (12 metre high X 12 metre long) work for the new Royal

Adelaide Hospital due for installation in July 2015; the other

an exhibition at the Prospect Gallery in November 2015. I will

include more details regarding these later.

Less demanding, but more enjoyable, is the Long Paddock venture.

Every Thursday I set out with Bill Morrow and Stephan Leishman

(occasionally Ian North) into the wilds of the Adelaide Hills

to draw and paint.

Mount Barker, Long paddock sketch, pen

and ink on board, 2914

Meanwhile I am attempting to finish my

second novel A Long Walk Through a Short History, a flaneur's

journey across the city of Brisbane.

To be continued .........

|

Avenue Bower # 1 120 x 900 x 60 cm Eucalyptus Sticks 2005

Avenue Bower # 1 120 x 900 x 60 cm Eucalyptus Sticks 2005